Measuring The Value Of Online Communities

By

James Christian Franklin, Professor Michael Mainelli, Robert Pay

Published by Journal of Business Strategy, Volume 35, Number 1, Emerald Group Publishing Limited (January 2014), pages 29-42.

James Franklin, Michael Mainelli and Robert Pay, The Z/Yen Group

[An edited version of this article appeared as "Measuring the Value of Online Communities", Journal of Business Strategy, Volume 35, Number 1, Emerald Group Publishing Limited (January 2014), pages 29-42.]

Abstract:

Online communities cannot be appropriately managed without understanding how to value them. The authors describe a model for assessing value and explain its possible divergence from statistical measures of community strength. Other factors might affect the level of value, such as the maturity of the community. The community manager’s importance in understanding, weighting and tempering the valuation is emphasised throughout.

Objective

The owners of communities often find it hard to estimate their value and to maximise their benefits. This paper aims to provide a set of measures that enable better understanding of online communities, their value and the strategic decisions best suited to them.

After an initial definition of terms and classification of online communities, a framework for assessing the value of communities is presented, enumerating benefits by their relationship to risk and reward. The disconnect between such benefits and the normal statistical measures of success is addressed, and the paper concludes with a short review of a range of other factors that should influence the valuation of online communities.

Terminology

For the purposes of this paper we will use the terms ‘visitor’, ‘member’, ‘manager’ and ‘owner’.

Visitors are those who visit a site but do not partake in the community, either actively or passively. They do not return to the site in any meaningful way and cannot be considered a part of that community.

Members are those who collectively constitute the community itself. There are a variety of members profiles, from those actively engaged in discussion at the centre to “lurkers” passively looking on from the side.

The Manager is the person or people who carry out the various administrative and managerial tasks involved in running the community. In practice, the manager may be an internal person or team, perhaps advised by a consultant or even fully outsourced to a third party.

The Owner is the entity that has ultimate responsibility for the community’s purpose and existence.

In contrast to the proceeding terms, ‘value’ is rather more contentious. For the purpose of this discussion, value is the offering of some benefit, or the absence of cost that would otherwise have been present.

Classification of online communities

In this paper, we will focus on online communities that meet five conditions: a sufficient number of members for the community to function; active engagement within the community; communication between the members on the site; a common interest, concern or question that forms the focus of the interaction between members; and a collection of practices or protocols that govern behaviour within the community.

The rigidity, transparency and threshold of these conditions will vary according to the type of community under consideration.

A brief survey of the literature provides four main types of possible classifications of online communities: Governance, Technical Operations, Member Behaviour and Strategy. Governance includes classifications of communities by their ownership, degree of regulation within the community, degree to which the community is open, and the concentration of online location. Technical Operations classify communities by the technical features utilised (video, blogs, forums, etc.). Member Behaviour can classify communities through their interest, benefits to be derived from membership, maturity of the community lifecycle, and the level of trust. Strategy offers a classification of communities through the purpose that they aim to achieve.

The axis most appropriate for this paper is ‘purpose’ because a community’s value will depend on what the community was set up to achieve.

This choice of classification axis does not exclude the relevance of other possible axes, as any community can be classified according to a number of different axes. The importance of the alternative axes are discussed later.

The evidence of worth model

Online communities can be classified by four key purposes, relating to the owner of the community [Mainelli, 2012 and Harris et al, 2002]:

- Thought Leadership: An online community used to generate, modify or present ideas. An example of this is Innocentive (https://www.innocentive.com), which exists to crowd source solutions to problems.

- Operations: An online community that seeks to address the system or operation of an organisation. This can take a passive form such as maintaining best practice, or an active form in mobilising members to bring about change. An example of this is Kiva (http://www.kiva.org), which enables the crowd sourcing of micro-financing to fund commercial initiatives in the developing world.

- Service Delivery: An online community that seeks to improve, develop or maintain the delivery of a service. This often takes the form of enabling members to offer feedback on products and services, but it can also be the provision of an extra or additional service. Examples of this are found in many of the branches of the Open University (http://www.open.ac.uk), where communities enhance the learning service offered by the institution.

- Building Relationships: An online community that seeks to create new, stronger or deeper relationships with its members. The benefits of this strategy include client retention, enhanced trust and increased reach. The community of Macmillan Cancer Support is a good example of this (http://community.macmillan.org.uk). These broad definitions of purpose are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, it is unusual for communities not to have elements of all four purposes.

These four types of online community have different relationships to risk and reward. Rewards can be enhanced, risks can be avoided and volatility in the service or product delivery can be reduced. Risk/reward profiles offer a framework for understanding the possible benefits of the online communities. This framework will also identify negative aspects or opportunities that are being missed, both of which are essential for any thorough assessment of value.In this way, the evidence of worth framework can be used to identify both actual and possible value for online communities.

Figure 1. Evidence of worth model for online communities

| Thought Leadership | Operations | Service Delivery | Building Relationships | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reward Enhancement | Innovation | Transformation | Enhancement | Cohesion |

| Volatility Reduction | Knowledge | Standards | Quality | Trust |

| Risk Avoidance | Reputation | Prevention | Vigilance | Reach |

Thought leadership

An online community can focus on thought leadership by means of innovation. Such a community will seek to generate new ideas, be it through the suggestions of members or the formation of a virtual workshop in which to critique or improve upon suggested ideas. An example of this is the forum for Joomla, an open source content management system that enables the creation of websites and other online applications (http://forum.joomla.org). The community’s owner benefits from the forum because it is used to suggest, discuss and improve upon new innovations. The absence of innovation results in poor or misleading ideas that fail to lead to, or distract from, new ideas for products or services.

Knowledge is achieved by gaining contacts, facts or information that will be of service to the owner of the community. An example of this is Social Media Today, a site based around blogging on social media for business (http://socialmediatoday.com). From the activity on the site, Social Media Today are able to identify key members within the community to call upon for commissioned blogs, reports or participation in their webinars. When this benefits is not achieved, the manager may make use of the wrong members and so fails to utilise the expertise available.

Reputation is sought through the displaying of ideas, arguments or beliefs, which build brand and enhance the standing of the community or its owner. This often takes the form of blogs displaying advanced or distinctive opinions. An alternative example is Danone, a multinational food corporation, which enhances its reputation through association with danone.communities, a site dedicated to reducing poverty and malnutrition worldwide (http://www.danonecommunities.com/en/home). An example failing to achieve this benefit is found in the BP Public Relations Twitter account, a phoney account set up in response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, which soon had over ten times the number of followers as BP’s official Twitter account.

Operations

Transformation is achieved by communities that address the operation of an organisation by mobilising its members. An example of this is Mumsnet, a forum providing peer-to-peer parenting support (http://www.mumsnet.com). Although not primarily a lobby group, the community has successfully launched campaigns like “We Believe You” Rape Awareness and Better Miscarriage Care, both of which seek to transform systems. A lack of transformation may result in unmonitored factions within the community starting campaigns that are opposed to the ethos of the community.

Standards of best practice within an organisation or system can be identified, debated or raised through online communities. An example of this is Hedgehogs, a site for the hedge fund and investment community (http://www.hedgehogs.net). The site allows for conversation about best practice and the sharing of progressive ideas about the sector. Without the standards benefit, unmonitored vociferous members could come to dominate the community and lead it away from best practice.

Prevention is a matter of avoiding adverse conditions or failures in the systems or operations. An example is the reduction of cost enabled by the community for Blip.tv, a site dedicated to hosting video series (http://support.blip.tv/forums). The forum enables members’ questions to be answered by other members, instead of using employee resources. Disregarding this benefit could incur an increase in resources required to monitor the community and respond to fake enquiries or spam.

Service delivery

Enhancement can be achieved through an online community developing or extending the service otherwise offered. One example of this comes from LinkedIn, a social networking site for people in professional occupations (http://www.linkedin.com). The community has a number of types of paid membership, which enable levels of activity beyond that offered by free membership. These enhance the service available to members whilst increasing the benefit to the community owner. A failure to achieve this benefit could result in no one taking up the additional service, effectively making its technical development a cost without return.

Quality of service can be maintained, developed or improved through online communities. An example of this comes from the community connected to the video-sharing website, Vimeo (https://vimeo.com/forums). Here posts on the forum for ‘Feature Request’ enable Vimeo to enhance the quality of their video hosting service according to the wishes and preferences of the members. A lack of quality could result in poorly monitored and sporadic reactions to forum suggestions, which would increase the volatility in the service provided.

Vigilance enables the manager of a community to minimize negative incidents through monitoring feedback on the community. This enables the community to be used as an early warning system for potential problems. Vigilance is in evidence on sites such as TripAdvisor, a user-generated travel-guide site based on reviews (http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk). The community allows for responses to reviews, which enables the levelling out of extreme opinions and a more reliable service. Without vigilance, negative incidents could occur, such as the recent case of Starbucks displaying unmonitored tweets at one of their sponsored London events, which resulted in a number of negative comments being broadcast about their non-payment of UK taxes [Telegraph, 2012].

Building relationships

Cohesion is achieved by online communities by strengthening or deepening the connections with and between its members. Because cohesion is responsible for a sense of community whereby members feel that they “belong”, it is one of the most ubiquitous benefits of successful online communities. This is greatly in evidence in news sites such as the online version of The Guardian (http://www.guardian.co.uk). Here members have vigorous exchanges about the topics of the articles, an activity which draws them closer to the community through participation in and engagement with its content. Cohesion is lost when members are estranged through vociferous voices at odds with the aims of the community.

Trust is the critical element in all online communities, as it enables members to open up to invest in and become a part of a community. Trust is central to communities such as Wikipedia, a free internet encyclopaedia edited by the members themselves (http://www.wikipedia.org). Although the nature of Wikipedia allows edits that might compromise the site, the overall reliability of the content encourages trust and drives further engagement by its members. A lack of trust results in members leaving the community.

Trust is unique amongst the other benefits because, as Mainelli (2009) noted, it is directly concerned with “relationships, communication and miscommunication,” all of which are essential issues for any community themselves. It is trust that underpins the possibility of all other benefits of an online community. Trust comes in four varieties:

- Technical: The technical side of the online space for the community is appropriate and reliable in terms of its functioning and usability.

- Governance: The members trust that their personal details and other such information is not going to be misused by the owner of the community.

- Administrative: The administration of the community is managed in an effective and swift manner, imbuing trust in the management of the site by the community members.

- Community: Members trust in the other members as worthwhile people to connect with through the community.

The analogy to financial stock exchanges has been proposed by Benjamin and Mainelli (2005) as a fruitful way to understand the role of trust in relation to online communities; for both stock exchanges and online communities, trust is what underpins the possibility of the thing functioning at all. If an online community loses its members’ trust in any of its four forms it will fail.

The analogy to financial exchanges points towards the essential nature of debit and credit inherent in a functioning community. A community can be understood as a network of indebtedness, member to member, member to owner and owner to member. Each member will be indebted to the owner for the space in which to connect with others, and they will enter into the community on the assumption that the other members will be worth their time and effort and that those other members also enter into the community in the same spirit. The owner is indebted to the members for all of the benefits enumerated in this paper. This suggests the potential relevance of online currencies; if an online community is built on trust in the same way as financial exchanges, then should it not therefore be able to support its own currency? Perhaps the possibility of floating an online currency could be the ultimate test of the vibrancy of communities of a certain size. Not all communities will be of sufficient size, and nor might they all be correct to aspire to it, but perhaps the concept of an online currency might be important to take on board when trying to understand the value of an online community.

Reach is achieved by gaining a significant portion of the market space for potential members. An example of this is Cat’s Corner, a community within the Whiskas cat food website, which offers an exploration of “the world of cats with fun and helpful articles and videos” (http://www.whiskas.com/CatsCorner/Articles). Articles in Cat’s Corner, including ‘Dr. Abigail on Cat Nutrition’ and ‘Where to Get a Kitten’, are effective ways of attracting in new audiences because they feature highly on online searches. This reach can turn negative through reaching of the wrong sorts of audience, through appearances in inappropriate online searches.

The relevance and importance of the different benefits will vary according to the community. This can be accounted for through different weightings being given to the measurements of the benefits. For example, in a community distinctly concerned with building relationships, such as Macmillan Cancer Support, it would be incorrect to weigh the cohesion benefit on par with innovation.

Measuring community strength

A strong or successful community will be a melting-pot of activity ready to take up and engage with on-topic ideas. The measure of this is usually presented to community owners by means of numerical statistics. These come in four varieties:

- Volume measures show the total number of visits to the site, and variations such as visits by new visitors.

- Activity volume measures show the total volume of broadly-defined activity on the site, including the number of log-ins, number of active members and bounce rate (i.e. the percentage of single-page visits to the site).

- Proportional activity measures are activity volume measures proportional to other relevant factors, such as the number of total members. Examples include: average time spent on the site, average number of posts, average depth of visit (i.e. the average number of pages viewed per visit), or average time between posts and responses.

- Weighted activity measures are proportional activity measures that have been weighted by their relevance to the specific purposes of the community. Examples include: average number of on-topic posts per member, average time between posts and on-topic responses, or the percentage of “active” members returning to the site.

The proportional and weighted activity measures are most relevant for assessing the strength of a community, as they give the best impression of the tone, connectivity and depth of the interactions on the site. The volume measures cannot be disregarded, however, as they are essential to establish that there is a reliable data set from which to derive the activity measures. A mix of all four types of measures is recommended. However, statistical measures alone are not enough to understand the value of an online community.

It is important to recognise the difference between community strength and value, shown by the possibility of being successful “for the wrong reasons.” For example, the Starbucks UK Facebook page was receiving nearly 700 on-topic and generally positive comments to announcements about the introduction of new flavours on 1 October 2012, but after 16 October all posts by Starbucks were inundated by negative comments about the company’s non-payment of UK taxes. Although large numbers of people continued to visit and engage with the site, their engagement is predominantly negative and aggressive, something that sets of numbers alone would not reveal. This Starbucks case exemplifies a conflict between reach and reputation, but conflicts between other combinations of purposes would have similar impact on the strength and the value of an online community.

Statistical measures of community strength are often only secondary measures of value, as they evaluate only the effects of a benefit rather the benefit itself. For example, although statistical measures are the primary measures of the strength of a community, they are only a secondary measure of the reputational benefit. This explanatory asymmetry between primary and secondary measures allows for a divergence between a community’s value and the measure of it, as the Starbucks case shows. Therefore, it will be best to link a primary measure to each of the key benefits identified for any online community. For example, the knowledge benefit of being able to identify useful potential contacts amongst members might best be measured on a manual count of new potential and actual contacts, rather than any automated statistical measure. It is better to take numerous primary measures than rely on a slim selection of secondary statistical measures that may diverge from an accurate accounting of value.

Appropriate measurements for value will vary according to the particular portfolio of potential benefits. It is the task of community managers to determine and weigh the measures appropriate in each case.

Understanding and managing your community maturity lifecycle

As well as determining the measures appropriate to the community, one of the principal tasks of the manager is to enable an appropriate interpretation of those measures. One of the foremost factors to grasp in this regards is the lifecycle of a community.

That value of a community does not directly map onto its strength is shown by the absence of a linear relationship between the number of members and the value of the community.

Figure 2. Linear relationship between the number of members and the value of an online community

That this linear relationship does not hold is due to the “network effect” whereby a linear increase in the membership of a community will bring about an exponential increase in its value. One of the earliest and most prominent statements of this is Metcalfe’s Law: the value of a system increases at a rate of the square of the number of members of that system.

Figure 3. Metcalfe’s Law

The exponential effects of this sort of rise in value are suggested by the increase in members on the strongest community sites. For example, Facebook took five years to gain its first 150 million users but then only a further eight months to reach 300 million, and LinkedIn took 16 months to get its first million users but only 11 days to add another million at the end of 2009 [The Economist, 2010]. However, Metcalfe’s Law should not be assumed, as Robert Metcalfe himself notes:

As I wrote a decade ago, Metcalfe’s Law is a vision thing. It is applicable mostly to smaller networks approaching “critical mass.” And it is undone numerically by the difficulty in quantifying concepts like “connected” and “value.” [Metcalf, 2006]

Metcalfe’s Law is relevant to the stakeholders of online communities as a rule of thumb by which to think of its value, rather than as an accurate measure of value. As Metcalfe himself also suggests, there are a number of key moments in the lifecycle of a community, which would create the need to adjust value expectations according to the community’s maturity within its lifecycle.

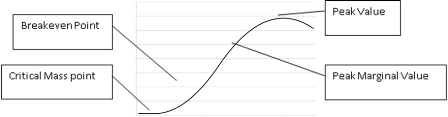

We suggest five stages to the lifecycle of a community: forming, growing, succeeding, ailing and moribund. These stages are marked by four transition points in the maturity of any online community:

- Critical Mass: This is the point at which ideas on the site will grow instead of wither. Here the community begins to take on a life of its own and to grow of its own accord. It is here that the community is felt to “begin to work.”

- Breakeven Point: This is the point at which the value of the community equals the investment put into it. This is the point at which, if measured in monetary terms, the community begins to offer a return on the cost of investment.

- Peak Marginal Value: This is the point at which the value added to the community as a whole by each additional member is at its maximum. Beyond this point every new member will each be adding less additional value to the community.

- Peak Value: This is the point of maximum value of the community. Any additional members beyond this point will decrease the overall value of the community.

This suggests a bell curve structure to the lifecycle. The distribution will not be completely even because once the peak value point is exceeded, it is unlikely that new members continue to join.

Figure 4. Lifecycle of an online community

The position of the breakeven point will vary with the type of community, according to both the costs and the returns. It is possible to calculate the breakeven point when considering a specific social media campaign, but for online communities in general it might be very hard to determine. This is because, although the investment will generally be made in terms that can be reduced to a monetary cost, the benefits are often too intangible and complex to be reliably tied to any specific monetary value. Therefore, it is important to temper the demand for a specific pinpointing of the breakeven point.

A point of peak marginal value may contentious, but a justification for it is put succinctly by Simeonov (2006):

"Size introduces friction and complicates connectivity, discovery, identity management, trust provisioning, etc."

If an online community is supposed to be based upon conversations, there is a point at which increasing the number of voices merely increases the noise, through which it is increasingly difficult to discern any meaningful content. It cannot be assumed that a community that works well with 100 members will work just as well with 100,000 users. Indeed, it is a question whether a community of a sufficient size ceases to be a community; we might consider the internet itself an example of something that was once a community but is today a utility.

The point at which peak marginal value is reached will vary according to the commitment or depth required of each connection within the community. An upward pressure on the volume of interactions will tend to adversely affect the value of each connection, thereby affecting the peak marginal value.

The peak marginal value marks the point at which something needs to change in order to extend the lifecycle of the community. Changes will be of one of two sorts:

- Administrative changes whereby the level of staff input into the running of the community is increased in order to offset the drag created by new members.

- Structural changes whereby changes are made to the structure or framework of the site so that the frictional issues can be bypassed. Examples of this include enabling sub-communities, introducing new features, or even a complete overhaul of the site.

Administrative changes can absorb only some of the drag caused by increased membership. When the stress of greater membership exceeds that reasonably open to administrational changes, structural changes will be required. Changes will push the peak marginal value to higher level of membership, but this point may again eventually be met and new changes will be required. The points of peak marginal value are the critical strategic decision points, where changes are required in order to allow for growth beyond current levels. If changes are successfully made, the point of peak value should ideally never be met.

A manager should be doubly aware of the lifecycle of their community: first, as a part of appropriately tempering the expectations of the measures of value and, second, as an indicator of where critical decisions are required.

Other factors affecting value

Maturity along the community’s lifecycle was one of the alternative axes by which to classify online communities. In the same way, the other possible classification axes are also relevant, as they contribute to a fuller description of any community. Therefore, the alternative axes will inform the sort of benefits that we should expect from the community.

The alternative size classification axis is important because there are often very real limits to the ultimate membership of a community. For example, Charity IT Leaders (http://www.ccitdg.org.uk), as a site for IT Directors of major UK Charities, has an ultimate limit to the number of possible members. Therefore, no amount of administrative or structural changes will ultimately shift the level of peak marginal value upwards. Such a limitation of the community is essential to recognise in any strategic thinking.

Temporality is relevant when communities experience activity that fluctuates according to different times of the year. The community linked to the annual Isle of Man TT motorbike races is one example (http://www.iomtt.com/forum.aspx). If due consideration is not taken of temporal factors misrepresentative measurements of value will result, endangering good strategic decisions.

The other possible axes of classification include: interest, membership benefits, degree of regulation, openness of membership, concentration in online location and technical features. Each of these will have an effect on the level of a community’s value. Some will be more and some less relevant for each type of community. It is important for managers to have a clear grasp of the details of their own community and to level their expectations accordingly.

Conclusion

“One size doesn’t fit all” when measuring the value of online communities. At each stage, if the best strategic decisions are to be made, the community and its contexts must be thoroughly understood. This paper has brought this out by our choice of purpose as the appropriate axis for classification, the selection from and weighting of the relevant elements from the evidence of worth framework, the statistical measures necessary to gain a fuller picture of the data, and the various other factors, such as the community’s lifecycle, which contribute to valuation of a community.

This paper has put forward three key points that should allow a structured approach to estimating the value of communities: firstly, a twelve-part model for classifying online communities by their purposes; secondly, a consideration of how these should be measured; and, thirdly, a review of some other factors affecting the valuation of communities.

Appendix 1: List of websites

The following websites are communities mentioned as examples in the paper:

https://www.innocentive.com

http://www.kiva.org

http://www.open.ac.uk.

http://community.macmillan.org.uk

http://forum.joomla.org

http://socialmediatoday.com

http://www.danonecommunities.com/en/home

http://www.mumsnet.com

http://www.hedgehogs.net

http://support.blip.tv/forums

http://www.linkedin.com

https://vimeo.com/forums

http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk

http://www.guardian.co.uk

http://www.wikipedia.org

http://www.whiskas.com/CatsCorner/Articles

http://www.ccitdg.org.uk

http://www.iomtt.com/forum.aspx

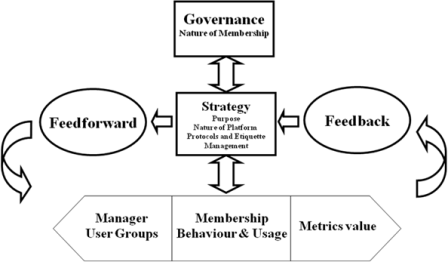

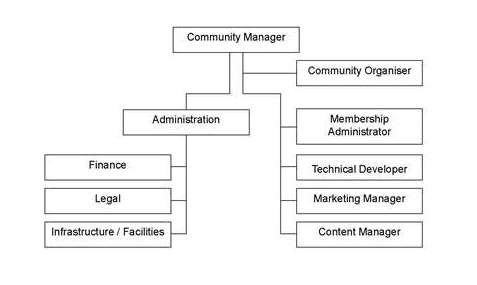

Appendix 2: Governance Model

Appendix 3: Online communities discussion guide

The following is a suggestion of the possible discussion points that could be utilised in a workshop in order to better understand an online community.

| Governance |

· Ownership issues · Nature of membership · Nature of trust within membership · Qualifications for access: type, size of organization, job title, role · Degrees of access · Cost versus free access · Constitution |

|

|---|---|---|

| Strategy |

Purpose of Community: · Building brand or business · Improving interactions with the membership or between the membership · Management of change/innovation: · Consultations on change, new services · Feedback – user groups · Forum for Innovation Etiquette and protocols – e.g. pre-vetting of comments, different levels of member participant, monitoring and retraction/redaction. Updating intervals Functionality of platform to support purpose and strategy |

|

| Membership Behaviour and Usage |

Core behaviours to be avoided/encouraged Behaviours to be measured: · Time spent on site · Frequency · Nature of organization/job title · Levels of engagement: o Voting or commenting on a specific proposal o Participation in trial o Viewing information |

|

| Value Metrics |

· Input resulting in change to proposed products or services · Engagement with decision-makers or target memberships · Cost saved in terms of poor service launches or other innovations · Commerce transacted as a result of the community · Opportunities to interact with target members beyond the community |

Appendix 4: Operational chart

Management of online communities is unlike other managerial roles in that it needs to be attuned to the members and their conversations. For this reason an organisational structure that allows for the greatest engagement with the content of the community is encouraged. The following suggestion is inspired by Frederick P. Brook Jr (1995) and his reference to surgical teams for his own considerations of programming units, which seems to align with the structural concerns of online communities also:

Bibliography

Benjamin, Leon and Michael Mainelli. (2005). ‘The Trends and Impact of Monetising Networks’. CIMTech.

Brooks Jr., Frederick P. (1995). ‘The Surgical Team’, in The Mythical Man-Month. Addison-Wesley.

Harris, Ian, Michael Mainelli and Mary O’Callaghan. (2002). ‘Evidence of worth in not-for-profit sector organizations’. Strat, Change 11 pp. 399-410.

Hunter, Gordon and Rosemary Stockdale. (2009). ‘Taxonomy of Online Communities: Ownership and Value Propositions’. Proceedings of the 42ndHawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Available from: http://www.deeprooted.ca/suncoast/Shared%20Documents/Portal%20Research/Taxonomy%20Online%20Communites.pdf [Accessed January 24, 2013]

Lazar, Jonathan and Jennifer Preece. (1998). ‘Classification Schema for Online Communities’. Proceedings of the 1998 Association for Information Systems, Americas Conference, pp. 84-86.

Mainelli, Michael and David R. Miller. (1988). ‘Strategic Planning for Information Systems at British Rail. Long Range Planning 21 (4) pp. 65 – 75.

Mainelli, Michael. (2003). ‘Risk/reward in virtual financial communities’. Information Services & Use 23 pp. 9-17.

Mainelli, Michael. (2006). ‘Take My Profits Please! Volatility Reduction and Ethics’. Gresham College, March 13, 2006. Available from: http://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/take-my-profits-please-volatility-reduction-and-ethics [Accessed February 11, 2013]

Mainelli, Michael. (2009). ‘Beyond Price: Trust me, I’m commercial!’. Gresham College, March 2, 2009. Available from: http://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/beyond-price-trust-me-i%E2%80%99m-commercial [Accessed February 6, 2013]

Mainelli, Michael. (2012). ‘Risk, Equity and Opportunity: The Roles for Government Finance’. Gresham College, December 4, 2012. Available from: http://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/risk-equality-and-opportunity-the-roles-for-government-finance [Accessed February 11, 2013]

Mainelli, Michael and Ian Harris, The Price of Fish. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

McAfee, Andrew. (2006). ‘Enterprise 2.0 Inclusionists and Exclusionists’. Available from: http://andrewmcafee.org/2006/09/enterprise_20_inclusionists_and_deletionists/ [Accessed February 6, 2013]

Metcalfe, Bob. (2006). ‘Metcalfe’s Law Recurses Down the Long Tail of Social Networks’. Available from: http://vcmike.wordpress.com/2006/08/18/metcalfe-social-networks/ [Accessed February 13, 2013]

Simeonov, Simeon. (2006). ‘Metcalfe’s Law: more misunderstood than wrong?’. Available from: http://blog.simeonov.com/2006/07/26/metcalfes-law-more-misunderstood-than-wrong/ [Accessed February 5, 2013]

The Economist. (2010). ‘Global Swap Shops’. ‘A world of special connections: A Special Report on Social Networking’ in The Economist, January 30, 2010, pp. 5-8.

The Telegraph. (2012). ‘Starbucks Twitter campaign hijacked by tax protests’, The Telegraph, December 17, 2012. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/twitter/9750215/Starbucks-Twitter-campaign-hijacked-by-tax-protests.html [Accessed February 20, 2013

Biographies: James Franklin, Michael Mainelli and Robert Pay

James Franklin

James Franklin has been at Gresham College since 2006 and is currently Communications Manager. The College has been proving free public lectures since 1597, making it London’s oldest Higher Education Institution, and today it offers nearly 150 free public lectures each year. Since the year 2000, the College has been offering this online, today with an archive of nearly 1,500 lectures spreading back to 1983. Amongst other communications roles, James leads the dissemination and promotion of the College and its lectures online: through the College’s own website, third-party websites, video hosting and collection sites, media stores and now mobile devices. James holds philosophy degrees from the University of Manchester and an M.Phil from King’s College London.

During 2013 James Franklin enjoyed a secondment at Z/Yen Group.

Professor Michael Mainelli

Professor Michael Mainelli is Executive Chairman of Z/Yen, the City of London’s leading commercial think-tank and venture firm. He co-founded Z/Yen in 1994 to promote societal advance through better finance and technology. He created and remains Principal Advisor to Long Finance, a movement addressing the question “when would we know our financial system is working?” He created the renowned Global Financial Centres Index as well as the Global Intellectual Property Index.

Previously Mainelli’s worked for several years as a partner and board member of one of the leading accountancy firms directing financial services and technology work globally, and serving on the board of the UK Ministry of Defence’s Defence Evaluation and Research Agency commercialising technology. A qualified accountant, securities professional, computer specialist and management consultant, Professor Mainelli won a 1996 UK Foresight Challenge award for the Financial Laboratory and a 2003 UK Smart Award for prediction software, was British Computer Society Director of the Year in 2005, and was designated a Gentiluomo of the Associazione Cavalieri di San Silvestro in 2011. He was a visiting Professor at the London School of Economics and lectures regularly at universities and schools.

He serves as a non-executive director of UKAS – the United Kingdom Accreditation Service, a nonexecutive director of Sirius Minerals plc – a potash firm, an Almoner of Christs Hospital – the charitable boarding school and as a Trustee of the International Fund for Animal Welfare. Professor Mainelli has published over 40 journal articles, 150 commercial articles and four books, including Clean Business Cuisine: Now and Z/Yen, and The Price of Fish: A New Approach to Wicked Economics and Better Decisions, both co-authored with Ian Harris. He holds degrees from Harvard, Trinity College Dublin and the London School of Economics.

Robert Pay

Robert Pay has extensive experience in both professional and financial services. His chief interest is building both business and brand for know-how rich businesses.

His roles have included being a Marketing Manager for a “Big Four” banking and securities practice, and a seven year stint as the Global Chief Marketing Officer of leading international law firm, Clifford Chance. He was Head of Marketing at the London Stock Exchange where he was responsible for the marketing launch of AIM, the smaller companies' market, on whose Board he served; he developed a successful marketing campaign aimed at attracting foreign issuers to London; and marketing of introduction of order-driven trading. He then ran the European arm of a US-based professional services consulting firm for several years before moving back in-house as Global Marketing Director of BSI Management Systems where he introduced an NPD process, and refocused the global marketing function on new product development. Immediately prior to relocating to the United States he was the Chief Marketing Officer for European law firm Taylor Wessing, where he worked with Z/Yen to create the Global IP Index.

Rob has been an associate of Z/Yen since 1998 and has worked on a number of assignments. He graduated from Oxford University in History and modern languages, and has an MBA with distinction from City University Business School together with the Market Research Society Diploma (Distinction) and the Communication Advertising & Marketing Foundation Diploma.