Caveat Emptor, Caveat Venditor: Buyers & Sellers Beware The Tender Trap (procurement)

By

Ian Harris, Professor Michael Mainelli, Haydn Jones

Published by Journal of Strategic Change, Volume 17, Number 1/2, John Wiley & Sons (Jan-May 2008), pages 1-9.

Professor Michael Mainelli and Ian Harris, The Z/Yen Group

Haydn Jones, Consultant with A.T. Kearney

[An edited version of this article first appeared as "Caveat Emptor, Caveat Venditor: Buyers And Sellers Beware The Tender Trap", Journal of Strategic Change, Volume 17, Number 1/2, John Wiley & Sons (Jan-May 2008) pages 1-9.]

Suppliers increasingly find themselves required to put in competitive tenders in order to win business; especially public sector contracts. Indeed, large organisations of all kinds, including NGOs, increasingly require their suppliers to go through structured tendering processes. But often those structured tendering processes are inappropriate for the procurement situation, leading to non-optimal results for both buyers and sellers. Ian Harris and Michael Mainelli of The Z/Yen Group, together with Haydn Jones from A T Kearney, examine “The Tender Trap”.

The Buyer’s Dilemmas

Clients often complain to us about the unreasonable and inappropriate demands of the public procurement processes required of them to win business; especially public sector contracts. Yet, often, the buying departments in those self-same organisations are adopting “public procurement”-style processes when purchasing.

There are genuine dilemmas for the buyer here. When awarding substantial contracts, procurement processes need to be transparent and demonstrably above board. Yet, while half-buried behind some extensive procurement process checklist, the buyer is often also hidden from any chance of thinking clearly about the choices available and making a wise decision. That is more than a little unfortunate, as making an optimal choice is essentially the buyer’s goal.

Structured tendering also tends to drive the innovation out of selling. In the light of a detailed specification of the products and/or services required, it takes a brave seller to tell the procurement people that they might have specified the job incorrectly. Far easier (and far more lucrative) to simply sell the things that have been have asked for. But it takes an equally brave buyer to confess to potential suppliers that the purchasing organisation is not entirely sure what it wants to buy.

Agency Theory, Information Asymmetries and Externalities

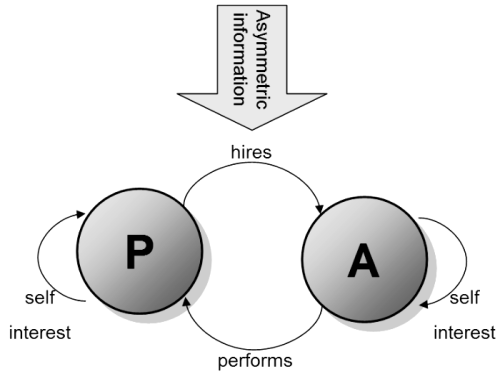

Other than the simplest buying and selling situations, procurement is subject to the principal-agent problem, or Agency Theory. In short, the problem stems from two issues that subsist in such transactions; the interests of the principal and the agent are not wholly aligned and there are usually significant information asymmetries between the parties, leading to substantial uncertainty and risk. The diagram below illustrates these issues.

Diagram One: Principal-Agent Problem

[Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Principal_agent.png]

Principal-agent problems do not only arise in procurement situations. Indeed, Agency Theory came to the fore when examining the principle-agent relationship in employment situations [1]. Practical applications of this theory include; performance related pay and stock option models, rationale behind principals encouraging tipping [2] and corporate governance frameworks [3] .

Principal-agent problems tend to be considerably more complex in circumstances where a large organisation is making a substantial procurement. There are several principal-agent relationships in play; between the buying organisation and the selling organisation, between the buying organisation and its own staff who are undertaking the procurement exercise for it. For example, the buying organisation often worries about the risk of corruption between its staff and the selling organisation. As a result, it might bring in a specialist third party to manage the procurement process for it; hey presto, another principle-agent relationship to manage. The selling organisation also might have multiple principal-agent relationships involved; for example the use of a third party to help to prepare the competitive tender. There is a great deal of room for information asymmetry, uncertainty, risk and foul play in these circumstances.

A further complicating factor is externalities. Externalities occur when a transaction has potential impacts on stakeholders beyond the parties involved in the transaction. Externalities are often present in public-sector tenders, indeed they are often the subject matter of the transaction when organisations are being asked to bid to take on public services. But any large-scale transaction is likely to include some externalities, so this factor also comes into play in business-to-business transactions. Coase’s Theorem suggests that it should be possible to reach efficient bargains despite externalities as long as transaction costs and information asymmetries are minimised [4]. But critics of Coase’s Theorem point out that such transactions are rarely low cost and frequently are subject to information asymmetries [5]. Indeed, in tendering situations, it can almost be used as evidence towards the mirror of Coase’s argument; given that transaction costs tend to be high and information asymmetries significant, it is very difficult to reach optimal bargains in circumstances where externalities are involved.

Where the procurement is substantial and varied, the problems and complexities described above are sometimes inevitable and unavoidable. Our concern is with the inappropriate and over-use of this formal style of procurement, despite its propensity to yield poor decisions and the great effort required by all parties concerned to attempt to manage the associated problems that arise through the use of such formal processes.

Real-World Examples

The risks associated with large-scale procurement are not for the faint hearted. You only have to look at what happened when the UK’s Department of Health opted to outsource its National Health Service Logistics division. The original £715 million ($1.4 billion) contract, advertised in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU) turned out to be worth a cool £3.7 billion ($7.4 billion) annually. The way in which the apparent and actual deal value was presented to hopeful suppliers, left the procurement process open to challenge from unsuccessful bidders. This put at risk the bid fees incurred by all parties over the two years it took to bring the deal to life, not to mention the opportunity costs.

It took some deft legal footwork for the Department of Health to scotch attempts to have the whole thing re-tendered. An example like this makes you realize what’s at stake when you enter the realms of public sector procurement. And its not just presentational oversights like this that can put the kibosh on the procurement process; in another example, the tendering of several hundred million pounds worth of public sector contractor spend was brought to an abrupt halt after a supplier questioned the legality of agreeing fixed rates of pay for the same types of services offered by contractors. The process had to be undertaken again, incurring three months of delay, ironically with no change in structure, or value realized from the process, save for some slight changes in wording to circumvent the challenge.

This is not just a problem for large-scale and public sector procurement. One commercial sector organisation we came across recently, using public sector-style procurement processes, managed to spend over a year to complete the tendering process for business worth just over £100K ($200K). We dread to think what the cost of the procurement process was; perhaps more than the contract value once all the hidden costs of the procurement process are taken into account.

Another example. A friend of ours sells design consultancy services. To protect his identity we’ll simply refer to this as “Nigel’s Story”. Nigel’s company was invited to tender by a UK-based environmental non-governmental organisation (ENGO). This ENGO, like an increasing number of NGOs, had adopted public-sector style procurement procedures.

As Nigel put it “they were asking for an enormous amount of information and this was just the pre-qualification questionnaire (65 pages long); I dread to think what the actual tender process would be like. A lot of the questions were obscure and could be interpreted in all manner of ways. It became clear at the open meeting that they didn’t really understand what they were asking for, nor did they understand the distinction between the myriad of ‘lots’ against which we were expected to respond.”

Nigel goes on, “the key to me is that this sort of process demonstrates that the buying organisation does not understand the market it is buying in. In the interests of standardised procurement, the buyers paid no attention to the credibility and track record of the companies involved. I suspect that many good companies were, like us, put off by these processes and simply declined to get involved. This leaves bodies like this ENGO using second rate outfits”.

Public sector procurement rules were introduced ostensibly to put all EU suppliers on an equal footing. The net result, however, is a process that is overly prescriptive, bureaucratic and one that attempts to parcel up similarly specified lots into work packages that can be compared on a like for like basis. This can be great for commoditised services such as telecoms – a recent public sector telecoms tender yielded more than 25% in overall savings opportunity – but not all goods and services provided by suppliers can be packaged up like this.

We set out below our thoughts on the various procurement types and styles that buyers might use, with the underlying thought that formal, structured tendering is only appropriate in the minority of cases.

Procurement Types and Styles

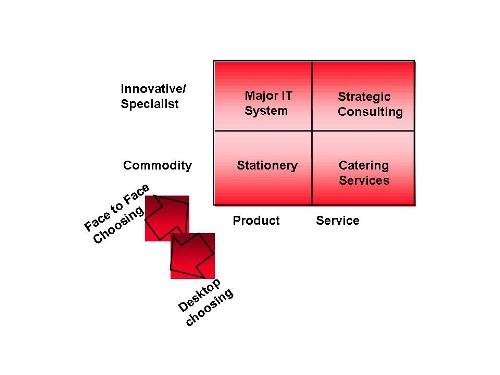

The diagram below illustrates procurement types with examples of each, using our old friend the two-by-two matrix.

Diagram Two: Procurement Types and Examples

The bottom left-hand corner of the matrix covers commoditised products. A good example is stationery. This type of purchase lends itself to back-office or desktop choosing, e.g. by catalogue.

The top right-hand corner of the matrix relates to more innovative, specialised and service-based offerings. An example dear to our hearts is strategic consulting. This type of purchase usually requires face-to-face choosing; good choices tend to need hands-on, investigative and/or iterative approaches.

The top left-hand corner of the matrix relates to those innovative and/or specialised purchases that are more product-oriented. A major IT system is a good example. In this example, a tender-based approach, combined with an element of hands-on selection, is often an appropriate way to make a good choice.

The bottom right-hand corner relates to the more commoditised service offerings. Catering is a good example. Here, an element of catalogue style choosing is appropriate, although this should be combined with some hands-on evaluation of service providers. In larger instances, formal tendering can be appropriate here.

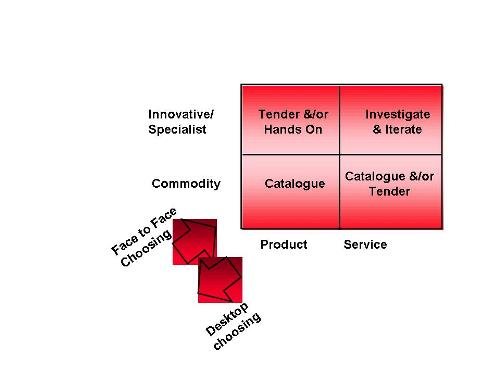

Diagram three illustrates the procurement styles in each of these categories:

Diagram Three: Procurement Styles

You quite often come across “tendering processes” for commoditised purchases, where the buyer is going to a great deal of trouble to try and run a proper process but cartels of sellers “fix” the process by providing inflated quotes for each other on a reciprocal basis. This bad practice is very common in vehicle repairs and property decoration contracts. To find best price, the buyer really wants to use negotiation, but sometimes finds itself hide-bound by its own procurement process until too late a stage to be able to negotiate best price.

At the other end of the spectrum, you often come across formal tendering processes for innovative and/or strategic services, even though it is nigh-on impossible to specify the services (often you don’t even know what you want to buy). The main problem in this instance is that the very process of specification and tendering is likely to drive away most if not all the innovation you seek, by putting off the more innovative suppliers and/or by encouraging suppliers to narrow their vision in order to comply with the specification and the tendering process. Nigel’s Story (above) is a typical example of this problem.

Organisations that model their entire procurement processes on public sector procurement rules, tend to know instinctively that the processes don’t work in all cases and sidestep their own rules when it suits them. We haven’t had the heart to tell Nigel that the very ENGO that caused him all that grief, recently procured some services from Z/Yen (albeit a small assignment) with no more than a simple letter proposal; no competition and certainly no onerous prequalification questionnaire.

Relationships, Buying and Shopping

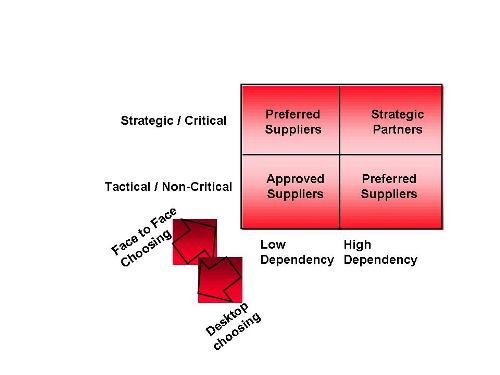

Another way for the purchaser to look at this problem is to consider the type of relationship it seeks with the supplier.

Good purchasing professionals will tell you that suppliers are segmented according to their business impact and the dynamics of the market that they are operating in. Suppliers need to be treated differently, depending upon whether they are Strategic Partners or merely Approved. The former implies a level of trust and co-operation, whereas in the case of the latter, you really don’t mind who the supplier is as long as they deliver on time, and on budget. Innovation would normally come from strategic suppliers, but such relationships by necessity are based on risk and trust.

Diagram 4 below illustrates this form of supplier segmentation.

Diagram 4: Supplier Segmentation

The existing public-sector style procurement processes do little to foster a trust based relationship that allows an innovation agenda to flourish; indeed they tend to achieve the opposite. A sense of this problem is contained within the graphic comments from the former head of a much needed billion pound healthcare IT transformation programme. Describing the project as a sled being pulled by a team of huskies he said “When one of the dogs goes lame, and begins to slow the others down, they are shot.” The problem was that under these circumstances they had real problems trying to shoot once of the larger dogs who ended up trying to sue the sled owners. There is not much trust and co-operation to be inferred from those comments and the actions that resulted.

One quite different way of looking at the above conundra is to think about procurement as a mixture of both buying and shopping. Formal procurement processes tend to be essentially about “buying”, but for many types of purchase there should be a significant element of “shopping” involved. We could harp on stories that suggest that “buying is from Mars and shopping is from Venus” but perhaps there are too many stereotype pitfalls in that line of discussion. However, the following table takes a (mostly) considered view on the characteristics of buying and shopping.

Table One: Buying and Shopping compared

| Buying | Shopping |

|---|---|

| Preconditioned | See possibilities |

| Often pre-decided | Often exploratory |

| Compare prices | Compare features |

| One-off process | Learning process |

| Quick process | Iterative process |

| Hunt down purchase | Tease out purchase |

| From Mars? | From Venus? |

Looking back at the matrices in Diagrams Two and Three, straightforward buying is quite possibly all you need in the bottom left-hand corner, “commoditised product” section. But almost anything else that you procure (most of the purchases and probably the most important purchases) benefit from elements of shopping as well as buying.

Let the Seller Beware

So far we have mostly examined “The Tender Trap” from the buyer’s perspective. But there are also substantial pitfalls for sellers. Putting to one side the obvious point that most bidders in competitive tendering processes do not win the business, even the “winning” organisation often finds itself losing, due to an affliction known as winner’s curse.

The principle of winner’s curse is that, in a competitive tendering situation, where the competitors have incomplete information about the exact costs and/or value involved, the “winning” competitor nearly always under-prices their bid, such that the “winner” is eventually disappointed. The disappointment might not be actual losses (although in many cases, on a full-costing basis it does result in real losses) but it does result in a lower than expected return. One intriguing and somewhat counter-intuitive element of the winner’s curse is that the larger the number of participants in the competition, the more pronounced is the winner’s curse effect6.

While economic theory suggests that rational contestants should price “known unknowns” into their bids, experimental situations demonstrate that participants can be familiar with the phenomenon of winner’s curse, yet repeatedly make the same mistakes in subsequent experiments. In the real world, we often see the same contestants caught out by the winner’s curse in fields such as mergers and acquisitions (they rarely add value) and auctions of scarce resources (for example the 3G bandwidth auctions).

While we might tut-tut at corporate executives hubris and/or anomalous decision-making behaviour, in many ways the phenomenon is even worse when experienced by NGOs, especially charities. In the UK, where increasingly public services are being contracted out to charities and/or commercial care providers, this is becoming a significant problem. Charities (perhaps unwittingly) frequently disguise their winner’s curse losses through hidden subsidies from donated funds on contracts that are supposed to be fully-funded. This is often hidden in overheads or infrastructure costs, where large public sector contracts (supposedly fully-funded) often put a substantial strain on already stretched charity resources.

Bid/No-Bid

Of course, there is no rule that says you have to bid for every opportunity that potentially falls within your “patch”. Indeed, in our view, one of the most likely reasons for people bidding in inappropriate situations is the mistaken belief that you need to assert your territory whenever a contract comes up in your field of work.

As adherents of our own advice, at Z/Yen (and many of our clients) assess opportunities using a “Bid/No-Bid Decision Matrix”, with which we assess the factors relevant to that critical decision – should we bid or not. A great many competitive opportunities fail to make the grade on the basis of this assessment. Naturally, the relevant factors vary from organisation to organisation. The following table is an extract from the Bid/No Bid Decision Matrix for a fictitious tender.

Table Two: Bid/No-Bid Matrix for Fictitious Tender

| Bid/No-Bid Decision Matrix | Opportunity: | Ref: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bid Factors | Bid Factors Scoring Range | |||

| Low (0-3) | Medium (4-6) | High (7-10) | Score | |

| Relevant experience | Core | 7 | ||

| Availability of resources | Average | 5 | ||

| Overall capability | Superior | 7 | ||

| Strategic Importance | Moderate | 6 | ||

| Our offering unique | No | 3 | ||

| Value of “marker” bid | Reasonable | 5 | ||

| Contribution | Full cost cover | 6 | ||

| Customer relationship | Well known to us | 7 | ||

| Competition | Open | 5 | ||

| Bid resources | Sufficient | 6 | ||

| Number of bidders | 3 or fewer | 6 | ||

| Market intelligence | Thorough | 8 | ||

| Total Score (Bid threshold 80) | 71 |

In our experience, you need to set the bid threshold reasonably high, as the winner’s curse phenomenon combined with the natural optimism of enthusiasts leads most people to over-rate rather than under-rate opportunities when using this type of matrix.

Sellers should revisit the Bid/No-Bid Matrix if the goalposts move, which they very often do in these tendering processes, and be prepared to quit if the numbers no longer stack up for you. Don’t make the mistake gamblers often make of being sucked deeper in to a game than intended – cut your losses by withdrawing from a winner’s curse bid.

A very rough and ready straw poll by your authors suggests that savvy sellers end up bidding for roughly 1 in 3 opportunities that initially get through the screening. That is why buyers invest a fair amount of time in “hand-holding” activities such as supplier conferences, regular communications and chaser calls to encourage suppliers to stick with the process.

For some forms of vital work there is little or no alternative to tendering. But when you do tender, you want to know as much as possible about the competition and the decision-making process. The “Bid/No-Bid Matrix” is actually a good discipline for finding out as much as you can about the process.

Who Really is the Customer in Tender World?

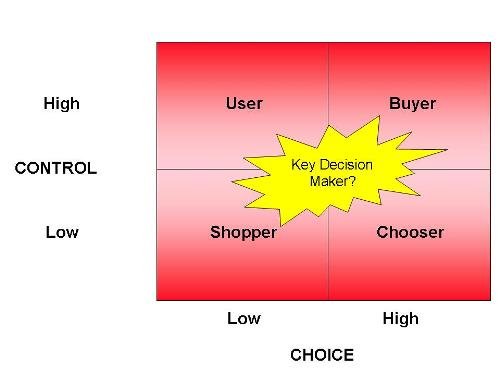

There is one aspect of the competitive selling situations that we consider to be vitally important although it is often overlooked, which is “who is the key decision maker”. In the late 1980’s two of us (Michael and Ian) worked for a firm that used the phrase BUSCK – “buyer-user-shopper-chooser-key decision maker”, a phrase that has always resonated with us. We cannot find a reference for it (so apologies to anyone who deserves credit for inventing BUSCK), but in any case the following diagram and text that follows is our own take on this form of analysis.

Diagram 5: Buyer–User–Shopper–Chooser–Key Decision Maker (BUSCK)

In theory a buyer has a great deal of control over the purchasing process and can spread the procurement net widely or narrowly. A shopper, on the other hand, while they might make on the spot decisions, is probably not controlling the procurement process and is probably only looking at choices within the constraints of options presented to them. A chooser is often a professional procurement person (sometimes an external consultant) who might ensure that the appropriate range of choices is presented but might have little control over the decision making beyond that. A user is the person or people who, on the other hand, might have a great deal of control over the procurement process (e.g. substantial input into writing the specification) but often has little input to the choices that are eventually made.

Of course, in many cases one individual fulfils more than one of those four roles. If one individual fulfils several of the roles, you might well have identified your key decision maker. But when the roles are well spread between several individuals, it can be very difficult to work out who the key decision maker is. Only occasionally does the decision really get made collectively by a selection panel; more frequently than you might realise there is a key decision maker who ultimately makes the decision. If you are speaking that person’s language you are more likely to win, so it is extremely helpful to at least try and identify who that person is and what will motivate them to select you.

It is important, where possible, to have formed your BUSCK assessment some time before the invitation to tender drops into your in-box. Ideally you want those prospective clients to know you well enough that they are only going to invite you to tender in circumstances which are genuinely suitable for both parties. And of course you would like the proposal to play to your strengths, which is all the more reason for you to seek dialogue before the specification is finalised.

Manifestos for Avoiding the Tender Trap

To summarise our thoughts on this subject, we propose two mini procurement manifestos for avoiding the Tender Trap, one for buyers and one for sellers.

Mini procurement manifesto for buyers:

- Aim to be professional and transparent when procuring. But “more tendering” does not equate with “more professional” and/or “more transparent”;

- Set criteria for procurement, but in most cases “window shop up front” so that valid criteria can evolve and emerge;

- When you seek innovation, avoid large and formal tendering processes. There are other ways of ensuring that the procurement is fair and transparent (e.g. meeting several suppliers up front but only inviting two or three to make formal proposals);

- Ensure that your organisation learns from procurement processes by formalising the learning part; strangely that is one part of the process that tends to remain informal and often is not done at all;

- Don’t choose suppliers merely on the quality of their presentations; you are very rarely seeking to buy presentation skills, yet very often suppliers are chosen on the quality of the presentation rather than the content.

Mini procurement manifesto for sellers:

- The sweetest bid of all is often not to bid – remember how often the winner will suffer from winner’s curse. Winner’s curses (unlike sour grapes) are best savoured when you’ve not bid at all;

- Know when to quit a tendering process, especially if the goalposts move in an unfavourable direction during the process;

- Ensure you have enough information about your prospective clients to minimise the risk of winner’s curse in your case;

- Bid when tendering processes should favour you, i.e. when you know that key decision makers at the prospective client are inviting you to bid, because they know that you actively seek such work and that you should be well-equipped to do the work well.

References

[1] Agency Theory Links - http://www.istheory.yorku.ca/agencytheory.htm

[2] What I Like About This Country is That it Has a Nice Level of Corruption, Mainelli, Michael, Gresham College (2007).

[3] Agency Theory and Corporate Governance: Review of the Literature From a UK Perspective, McColgan, Patrick, http://accfinweb.account.strath.ac.uk/wps/journal.pdf (2001).

[4] "The Problem of Social Cost.", Coase, Ronald H. Journal of Law and Economics. 3 (1960).

[5] http://www.huppi.com/kangaroo/L-chicoase.htm critical essay with several relevant references.

[6] The Winner's Curse, Thaler, Richard H., Princeton University Press, 240 pages (reprint), (1994).

Ian Harris and Professor Michael Mainelli are Directors of Z/Yen Group Limited, a risk/reward management practice, dedicated to helping organisations prosper by making better choices (www.zyen.com). Z/Yen clients include blue chip companies in banking, insurance, distribution and service companies as well as many charities and other non-governmental organisations. Haydn Jones is a consultant with A.T. Kearney who specialises in cost reduction. He has worked in both the public and private sector in various roles and has a specific interest in Procurement.